The Bedfordshire Regiment in the Great War

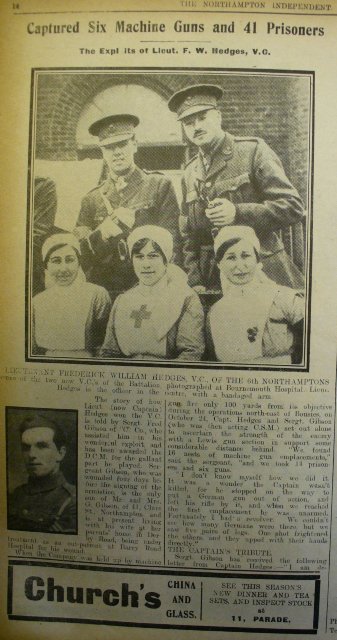

Frederick William HEDGES, V.C.

|

|

Frederick Hedges was also known as Fred, Freddie and Bill. His cousins Jeff and Jenny have been kind enough to share their research with the site. Added to which Steve Beeby's information has made the story both interesting and sad, as seems to be the case with many V.C. winners.

Frederick William Hedges was born on the 6th June 1896 at Umballa in India. His father was Henry George Hedges who was 'born at Sea, Bengal Bay' around 1857 and his mother was Mrs Harriet Eliza (nee Loader) Hedges, born in India around 1865. Henry has served as a Bandsman in the 12th Royal Lancers at Bangalore, later serving as the bandmaster in the 18th Hussars. In 1901 the family were living at 24 Landsdowne Road, Hounslow, Middlesex. Henry was a superintendent (assurance) and Freddie was the seventh of nine children. He was later educated at Grove Road Boy's School, and Isleworth County School.

Freddie enlisted into the Queen Victoria's Rifles on the 6th August 1914 at Davies Street in London. He was posted as Rifleman 2182, to the 1st/9th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Queen Victoria's Rifles) on 8th August 1914 and left for France with the battalion in the 5th November 1914. After involvement in the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, Freddie was admitted to hospital in France with frostbite on 28th January 1915 and evacuated to England on 29th January 1915. Having recovered, he was transferred to B Company, 3rd/9th Battalion London Regiment (Queen Victoria's Rifles) on 15th April 1915.

The 6th July 1915 saw him commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Bedfordshire Regiment and he went to the Felixstowe School of Instruction on the 10th July, before joining the 9th Reserve battalion as a Musketry Officer. After a year training recruits in musketry, on the 2nd September 1916 he left for France again, joining the recently arrived 6th battalion.

Whilst serving in the 6th battalion, Freddie was engaged in the Battle of the Ancre between the 13th and 15th November 1916 and the Battle of Arras in April 1917. On the night of the 10th April 1917, he was wounded in the right hand by shrapnel whilst the battalion dug in astride the Le Bergere crossroads, a few yards south of Monchy le Preux in the snow. He was evacuated to Rouen, thence to England aboard the St. George on the 19th April and was admitted to No.5 General hospital in Portsmouth.

The 12th October 1917 saw him returned to light duties with the 3rd Reserve battalion as a machine gun instructor and his promotion to Lieutenant came through from the 1st July 1917.

Freddie returned for a third tour on the western Front, arriving on the 25th September 1918. As his battalion had been disbanded that summer, he was attached to the 6th Northampton's, where his service on the front lines would end. He served in the final battles of the war, specifically at the Battles of Epehy on the 29th September, the Selle on the 23rd and 24th October and finally at Sambre on the 4th November 1918.

|

His citation from the London Gazette of 31st January 1919 reads: "For most conspicuous bravery and initiative during the operations north-east of Bousies on the 24th October, 1918. He led his company with great skill towards the final objective, maintaining direction under the most difficult conditions. When the advance was held up by machinegun posts, accompanied by one Serjeant and followed at some considerable distance by a Lewis-gun section, he again advanced and displayed the greatest determination, capturing six* machine guns and 14 prisoners. His gallantry and initiative enabled the whole line to advance, and tended largely to the success of subsequent operations." The book 'V.C.'s of the First World War' reads: "To the north-east of Le Cateau on 24th October 1918, Captain F.W. Hedges of the Bedfordshire Regiment, attached to the 6th Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment (54th Brigade, 18th Division), gained a V.C. when his battalion was attacking north-east of Bousies. They were ordered to advance as far as the hamlet of Hecq, on the south-western edge of Mormal Forest. The advance began at 4 a.m. with A and B Companies advancing 500 yards over wooded country, which was very difficult terrain. C and D Companies then passed through their lines. C Company, under Captain Hedges, reached Hecq at about 6 a.m., only to find it very strongly held by the enemy, who immediately launched a counter-attack. The Lewis-guns dealt with this attack, but when the company emerged from the edge of the wood they found their way barred by two German machine guns. At about 2 p.m., on hearing that the line on his left was intending to make a determined advance, Hedges decided to move also. With the help of Sgt. Gibson, he managed to capture the machine guns and some prisoners". The 18th Divisional History adds of the episode: "Hedges' company was on the right of the 54th Brigade front. It was held up by six machine gun posts on a hill opposite. Hedges made up his mind to clear these posts. Armed with a revolver and carrying a cane*, which he waved when he wanted his men to dash forward, Hedges crawled up the hill under cover of a hedge. A sergeant [13974 Sgt. Fred Gibson] was with him. A Lewis-gun section followed some distance behind. Breaking cover, Hedges killed the first machine-gunner. Then he worked his way along the crest of the hill and dealt with three more machine gun posts, taking the feed-blocks out of the guns and securing altogether fourteen prisoners. The Lewis gun section came up to help. All the six Boche machine gun posts were captured, and as suddenly as it became clear that the three companies of the 6th Northamptonshires that had been checked near Bousies Wood Farm, had by now worked round the enemy from the north, the German resistance collapsed. The 2nd Bedfordshires and the 55th Brigade swept forward to seize Renuart Farm, and by 6 p.m. two companies of the Queens and East Surreys - cyclist patrols were used on this occasion - had got as far as the church in Robersart. As the Germans retired the French inhabitants braved the shelling and came out of their cellars to welcome our men. There were smiles and excited shouts, and hot cakes and potatoes for the Queens and East Surreys that night." In what would be the final battle of the war for his battalion, Captain Hedges was, ironically, wounded again. During the fighting at Mormal Forest on the 4th November 1918, Freddie was wounded in the right side of the scalp - "a three and a half inch crack in the skull" according to Sergeant Gibson - and a "through and through" bullet in his right shoulder. He was evacuated back to England, arriving at Southampton on the 8th November and heard the war had ended from a hospital bed in England. Captain Hedges was awarded the Victoria Cross by the King at Buckingham Palace on the 15th May 1919 and was appointed the Commandant of No.8 POW Camp on the 19th June. On the 26th July 1919 Freddie married Mollie Lorna Kenworthy (see below) but soon afterwards he suffered compound fracture of right leg in an on-duty collision between his motor cycle and a car (driven by the managing director of Leyland Motors as it turned out) at Fulwell, England on 27th September 1919. Subsequent medical examinations revealed the fracture had healed but other remarks show, with hindsight, that Freddie was not entirely well, probably after his experiences in the war. |

|

Mollie Hedges |

On 5th February, 1924, Mollie gave birth to their son, John Grosvenor. For Mollie, it was a difficult birth and (sadly in retrospect) they avoided her having another pregnancy. They were a contented family group and a year or so later they relocated from her parent's home to one of their own in The Avenue, Sunbury. With the exception of the death of Freddie's father at the end of 1936, it seems to have been a period of contentment as their son grew.

In 1939, Freddie was elected Chairman of the Teddington Branch, British Legion, having served previously as Vice Chairman. But in September, the Declaration of War was to cast a dark shadow on their lives. Freddie promptly attempted to re-enlist but he was upset at being rejected, while Mollie was deeply upset by his not consulting her nor even mentioning his intention to her beforehand. It was to remain a lasting sore in the relationship. He went on to become a Civil Defence Coordinator and as Chairman of the British Legion Teddington Branch he was in charge of the Annual Remembrance Day Parade in 1941.

4 days later, on the evening of 13th November 1941, John left home as usual, in full equipment for duty. As his War duty, their son John had joined the local, 31st Middlesex, Home Guard Unit, becoming a member of the Upper Thames Shore Patrol. On this occasion though, he was going via a friend's Birthday Party at Thames Ditton, South of the River. From the Party, taking the shortest route, he arrived at Sunbury Lock, at about 2 am, on the 14th. His colleague on duty, duly rowed across from the Middlesex bank and collected him. A few yards from the destination landing stage, John noticed his feet getting wet; water was being taken in. They both stood up and the dinghy capsized, throwing them in the River. The Ferryman swam to the stage, removed his greatcoat and attempted then, unsuccessfully, to find John before reporting the accident. The Police subsequently dragged the River in that area, a particularly deep and fast flowing section, a number of times with no success.

A month later, 13th December, a body was reported floating in the backwater of a downstream island. It proved to be John's and, apart from his rifle and 'tin helmet', was complete with all his possessions. John could not swim well; the ferryman had not been experienced and, finding the usual boat with a damaged rowlock, he had taken a nearby small dinghy. A former neighbour formally identified the body. The finding of the Coroner's Inquiry was Accidental Death due to Drowning. The body was cremated at the Mortlake Crematorium on Friday, 19th, and the Death registered the following day.

John had been the focal point of each of their lives and, inevitably, the loss and its circumstances placed added strain on the marriage relationship, one that would not have been helped by their remaining in the local area with its constant reminders. In the Office, Freddie was much appreciated and, in 1942, the Company offered him the position of Branch Manager of their Leeds Office - promotion with relocation. His subsequent celebratory drink(s) led to him being charged with being Drunk-in-charge. The Magistrates accepted his Plea - based on the then Medical Opinion that Head injuries were often associated with increased susceptibility to alcohol - and dismissed the case.

In Leeds, he continued his Rotarian and British Legion associations and his support for former Servicemen. Mollie however was less tolerant of the more industrial nature of the area and isolation from her friends. Not that they were completely isolated. His position allowed him some latitude, and he was called upon to return to the London area for meetings. On at least one of their visits, in 1947, they were 'snapped', having called in on Mollie's younger cousin (her former bridesmaid) and her family at Hemel Hempstead. In or before Autumn 1949 they, and his widowed mother-in-law, relocated to the more pleasant surroundings of Harrogate, where Mollie's mother died in 1950.

|

Fred and Mollie's wedding in 1919

|

|

Freddie had taken up his father's habit of a drink of beer, occasionally two, recognising and making allowances for any lunchtime intake resulting from entertaining clients. On the 10th Anniversary of John's death however, he was charged once again with being Drunk-in-charge. When the case was heard, he was already in a Clinic receiving treatment. This Magistrate was not sympathetic to his plea, as put by the Company's Solicitor. He was fined £50 and had his Driving Licence suspended for 2 years.

Within 2 days of being charged, he had accepted the Company offer of private treatment in a local Clinic at their expense and had been admitted. His treatment seems to have been based on the then Textbook opinion of a link between head injuries and sensitivity to alcohol. Having signed an Alcoholic's Promise to abstain, his treatment may have comprised little more than a course of anti-depressant medication, and a few sessions each of Counselling and Occupational Therapy while in the Clinic. He was discharged late in January 1952.

At the end of February, he wrote a progress letter to the Clinic Physician. At the beginning of the month, he had kept an early appointment in London with the Governors. They still felt he should return to the London area; he had argued against this, believing that his anxieties had been resolved and that all his important friends and connections in Yorkshire, wanted him back. The General Manager had then visited the Leeds Office. In Freddie's own words:

"When a Yorkshireman has once accepted you he doesn't fail to give you a helping hand when necessary. Without my knowledge many of them wrote to London expressing their view. Last week my General Manager came up and interviewed a wide cross-section of these people and others, and came to the conclusion that it would be safe to recommend to the Governors I should resume duties here."

He returned to work the following Monday, 3rd March, 1952. Two years later, about the end of March 1954, he retired on the ground of ill health. His (now late) colleague and successor was of the opinion that the Governors maintained their wish for him to return to a London area appointment albeit reducing their pressure. Mollie on the other hand had never fully accepted life away from the London area although, having her widowed mother with them until her death in 1950, had ameliorated the situation.

Mollie's view of Freddie was that he had been depressed ever since their son's death and treated for nervous anxiety most of that time. Much of the time through May 1954 he had been confined to bed, being visited daily by his GP. On the 27th he had seemed much better and was allowed to get up; and during that day and the 28th, and the morning of the 29th May 1954 he had seemed quite well, in good spirits, and cheerful. She had left the house about 10.30, that morning, leaving him in the house. When she returned about 45 minutes later, on going in to the house she saw him hanging from the landing newel post.

The Ambulanceman was the first to respond to her Emergency 'phone call. He cut the body down and called the family GP who examined it. On his arrival, the Police Officer recorded details of the scene in his report. After the Inquest, having found that Bill had taken his own life while the balance of his mind was disturbed, the Coroner was quoted as saying "It was tragic that the holder of the highest honour for gallantry, the Victoria Cross, should end his life in this way."

At his cremation at the Stonefall Crematorium, Harrogate on the 2nd June 1954, the chief mourners were his wife and elder sister (his childhood nursemaid), a few close friends, and his GP. The overwhelming majority present included his former colleagues and members of the local (Leeds & Harrogate) Rotary Clubs and the Insurance industry. His ashes were collected on behalf of his widow and sister who are believed to have scattered them discretely over the flower beds of the local public gardens in which he had enjoyed walking.

The morals of that time meant that there was no discussion of him and even mention of his name was avoided. However, Mollie, and later Madge (her main beneficiary - her young cousin and former bridesmaid), did keep items that identified him - portraits of the newly commissioned 2nd Lt, and the new Captain at his desk, and a small plaque from a presentation to him by the Old Boys of the Isleworth County School.

Frederick Hedges' V.C. and other medals are held by the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regimental Museum in Luton.

Site built by Steven Fuller, 2003 to 2023